Visual Journal- Sahel

⬇️ The journal is divided into sections by country. Scroll to read and view each part.

There is a certain magic in the Sahel — a raw, ancient beauty that pulses across the desert.

The land is dry, yet full of life. It clings to the edge of the horizon, where tall grasses conceal more than shade, and the air hums with silence.

As a passerby, crossing the arid land, I would watch through the car window as human figures emerged from the brush — quiet, dignified, almost timeless. They appeared like mythic, ancestral presences moving through the stillness, half-hidden behind the tall grass.

These fleeting images often framed the deeper shifts unfolding around me. Between 2020 and 2024, I found myself living through many of the Sahel’s defining moments — revolutions, transitions, the collapse and rise of governments. I’m still not sure how it happened, but it felt as though history was unfolding in real time, and I was standing quietly inside it.

There was always something unresolved in the air — that turning point when people begin to reclaim their destiny, to decide they will no longer be ruled by those who betray their hopes.

Life here is marked by hardship, by displacement, and by conflict often left out of the headlines. And yet, there is something enduring, something that refuses to disappear.

CHAD

Evenings in Chad carry a strange kind of beauty — a stillness that softens the city, making it feel almost gentle. At that hour, even this half-formed, heavy place seems touched by grace, bathed in the rose-gold haze that spreads slowly across the sky. As the sun begins to sink, the edges of the streets blur into shadow, and the city, usually dry and weary, feels momentarily transformed.

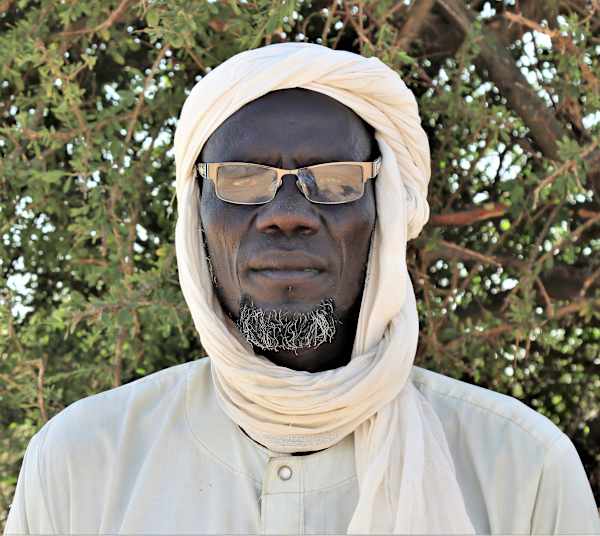

It is that time when, no matter where you pass, you hear the low, melodic chanting of the Tidjaniya. Wrapped in white cloth, their slow, rhythmic chants drift through the streets until the sun disappears completely.

So the end of the day finds me walking through this fading light — among men in turbans deep in prayer, and young men stretched out on the ground, their voices low, their movements unhurried. The scent of burning charcoal and hookah hangs in the air, mixing with the murmured chants and the distant songs of birds.

I walk through the rose-gold dusk, the clay walls of the houses still warm and glowing softly. Memory drifts in, uninvited but gentle — images of a life not so distant, yet already changed. I walk through this quiet evening light, not longing for the past but carrying its echo.

A lizard pauses to stare at me with strange curiosity. The city has turned purple. The chanting has grown louder. A breeze rises from the desert and begins to stir the dust in spirals across the road.

Before the city is swallowed by darkness, I say goodbye to the lizards and turn back. Soon, the chanting will stop, and the young men will drift into sleep on their woven mats.

The nights in Chad are grey.

So is the life of its people.

NIGER

In Niamey, when you walk along the river, the scent of mint fills the air.

The fertile soil along the banks of the Niger is planted with mint, parsley, and celery — but it’s the mint that overpowers everything. I often stop by the river, close my eyes, and breathe deeply, as if the earth and the water are embracing me.

Pirogues glide across the surface of the river, and the handmade gardens on its banks — green patches of life — speak of persistence.

A group of young men prepare to play football and invite me to join. I decline gently, as night is falling.

Children play with homemade wooden foosball tables and ask me to join them too. A girl hugs me. The women greet me with warm handshakes. The men offer tea. A grandmother hands me a freshly fried samosa.

I accept their sweets, their kindness, and their embraces.

The city is turning dark. I am where I shouldn’t be — in a place without lights, without maps, where no one knows what the dark might hold.

People stare with quiet curiosity. I wander through narrow alleys that open onto more alleys, mud huts, and open rooms without roofs.

People greet me along the way. And in that moment — in this dusty, painfully poor desert land, where having nothing is already too much, and where fear hangs like a weight — I feel safer than I ever have.

May God grant them the paradise they will never find on earth.

Burkina Faso - La Terre des Hommes Intègres

As I left Ouagadougou, with its wide boulevards and dust-choked traffic, the landscape turned harsher, the soil darker, redder.

It felt as though blood had seeped deep into the ground. Even the moon at night seemed to carry a red shadow.

I drove past endless barren stretches, scattered with half-built brick houses baking under the sun.

I kept wondering who had dreamed inside these walls — what kind of life had been imagined, and why it was never lived.

What interrupted the building of these homes? What stories were left unfinished?

In the rugged terrain of central and northern Burkina Faso, people’s faces were carved like stone. And sometimes, it felt like they disappeared back into it.

North NIGERIA - In the land of Boko Haram

I look around me. The children glance at me with timid smiles, the adults with fierce curiosity.

I can feel it—something is different here. The people are visibly worn down.

The children are malnourished, most of them covered in scabies and skin infections. The adults are skeletal, their eyes burning with malaria.

In one corner of the camp, a group of about thirty women and children sit outside a building. All of them frail, filthy, exhausted.

The children cough, their little bodies smeared with dirt and waste. The women arrived at the camp two weeks ago. They were freed by the Nigerian army from the hands of Boko Haram.

The Islamists had attacked their village and abducted them, dragging them deep into the forest, where they were held captive for over a year—along with their children.

Most of the babies I saw were born during their captivity.

The smallest was just ten days old, born here in the camp.

The stigma is immense. The women refuse to say whether their children are the result of rape.

But their frightened eyes say much more than words ever could.

One woman approaches me. She’s holding a baby, and instinctively I raise my camera to take a picture.

Only then do I notice the pain on her face. I lower the camera to the ground.

The baby looks like a newborn—but he’s eight months old.

He struggles to breathe, his tiny chest trembling with the effort to stay alive.

I don’t need to be a doctor to know he won’t survive many more hours. They tell me the clinic is closed.

That the mother has to wait until tomorrow.

That people aren’t allowed to leave the camp to go to a hospital.

That no doctor can come here.

The child is dying—right there in front of us—while I listen to all the explanations.

The child is dying, and we sit quietly discussing when, and if, the clinic might open.